Generic drugs are everywhere. They make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., yet they account for just 17% of total drug spending. That’s not a fluke. It’s the result of a well-oiled economic machine built on competition, patent expiration, and smart policy. But here’s the catch: not all generics are created equal. Some cost five, ten, even twenty times more than others that do the exact same thing. And if you’re trying to decide which drug to cover, which to prescribe, or which to push for in a hospital formulary, you need more than just a price tag. You need cost-effectiveness analysis.

What cost-effectiveness analysis really measures

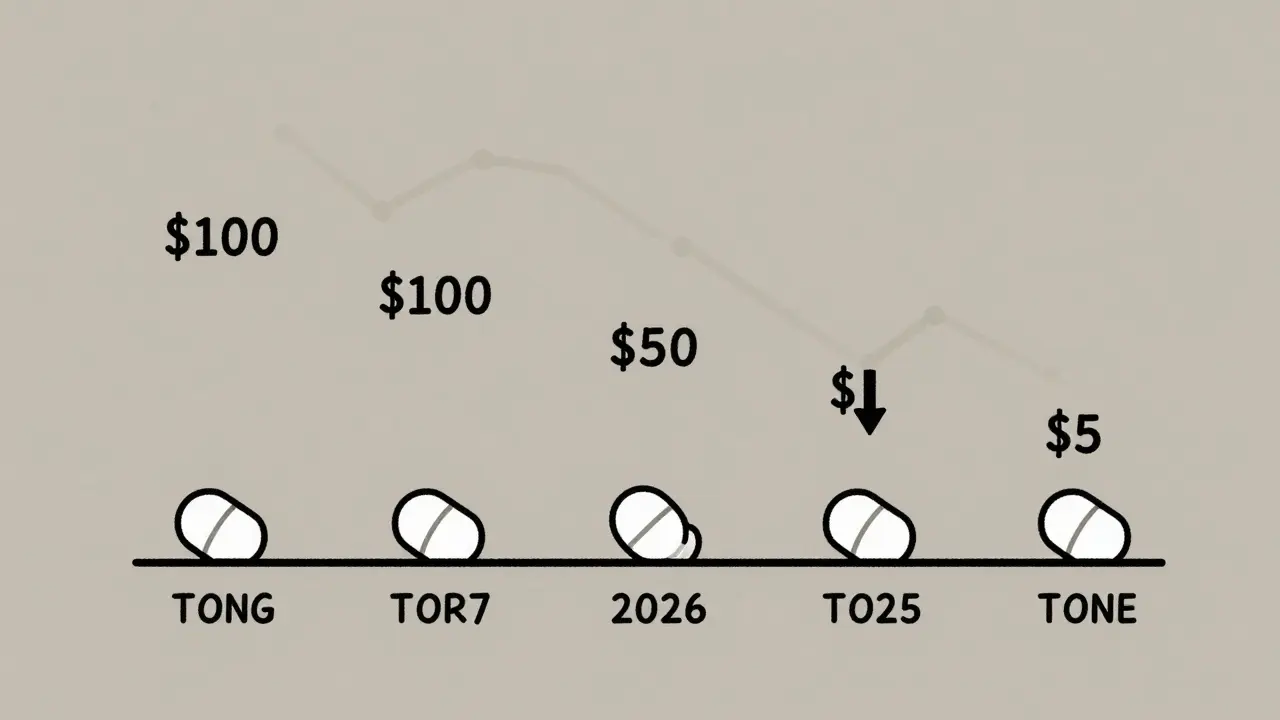

Cost-effectiveness analysis, or CEA, isn’t about finding the cheapest drug. It’s about finding the best value. That means comparing how much a treatment costs against the health benefit it delivers. The most common way to measure health benefit? Quality-adjusted life years, or QALYs. One QALY equals one year of perfect health. If a drug extends your life by two years but you’re bedridden the whole time, it might only add 0.4 QALYs. If another drug keeps you active and independent for those same two years, it adds 2 QALYs - even if it costs the same. For generics, CEA asks: does switching from a brand-name drug to a generic save money without losing health outcomes? The answer is almost always yes. When the first generic hits the market, prices drop an average of 39%. When six or more generics compete, prices plunge over 95% below the original brand. That’s not speculation - it’s FDA data. But here’s where it gets messy. Not every generic is a direct copy. Some are different formulations - extended-release, chewable, liquid - and those can cost more. Others are in the same therapeutic class but aren’t identical drugs. A generic for metformin might be cheaper than a generic for sitagliptin, even though both treat type 2 diabetes. CEA helps you sort through that.The hidden cost traps in generic pricing

You’d think once a drug goes generic, the price would stabilize. It doesn’t. A 2022 study in JAMA Network Open looked at the top 1,000 most-prescribed generics and found something shocking: 45 of them were priced 15.6 times higher than other drugs in the same therapeutic class that worked just as well. These weren’t brand-name drugs. They were generics - just overpriced ones. Why? Because price isn’t always set by competition. Sometimes it’s set by middlemen. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) often profit from “spread pricing” - they negotiate a lower price with pharmacies, then charge insurers a higher price, pocketing the difference. That means a $10 generic might be billed at $40. The insurer pays more. The patient pays more. The PBM wins. The patient loses. Even within identical drugs, prices vary wildly. Two pills of the same generic metformin, made by different companies, can cost 1.4 times more than each other. That’s not because one is better. It’s because of distribution deals, formulary placement, and lack of transparency. CEA cuts through this noise. It doesn’t care who makes the pill. It only cares: does this drug give you more health for your money?How ICERs reveal real value

The key metric in CEA is the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio, or ICER. It tells you how much extra you pay to get one extra unit of health benefit. For example:- Drug A costs $100 and gives you 0.8 QALYs.

- Drug B costs $150 and gives you 1.2 QALYs.

Why timing matters more than you think

Patent expiration isn’t a single event - it’s a cascade. When a brand-name drug loses exclusivity, the first generic drops the price. Then the second one comes in and drops it further. By the time you have five or six generics, the market is flooded. Prices collapse. But if your CEA uses today’s price as the baseline - without modeling what’s coming next - you’re making decisions based on a snapshot from five minutes ago. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) warns that failing to model patent cliffs creates “pricing anomalies.” It biases analysis against generics. Why? Because if you assume a drug will stay expensive, you’ll think switching to it is a bad deal. But if you know it’s going to drop to $2 next month, the real value is hidden. This is why smart health economists don’t just look at current prices. They model scenarios: What if two generics enter in six months? What if a biosimilar arrives next year? What if the VA negotiates a bulk discount? They build forecasting models that factor in market dynamics, not just static data.Therapeutic substitution: the silent savings opportunity

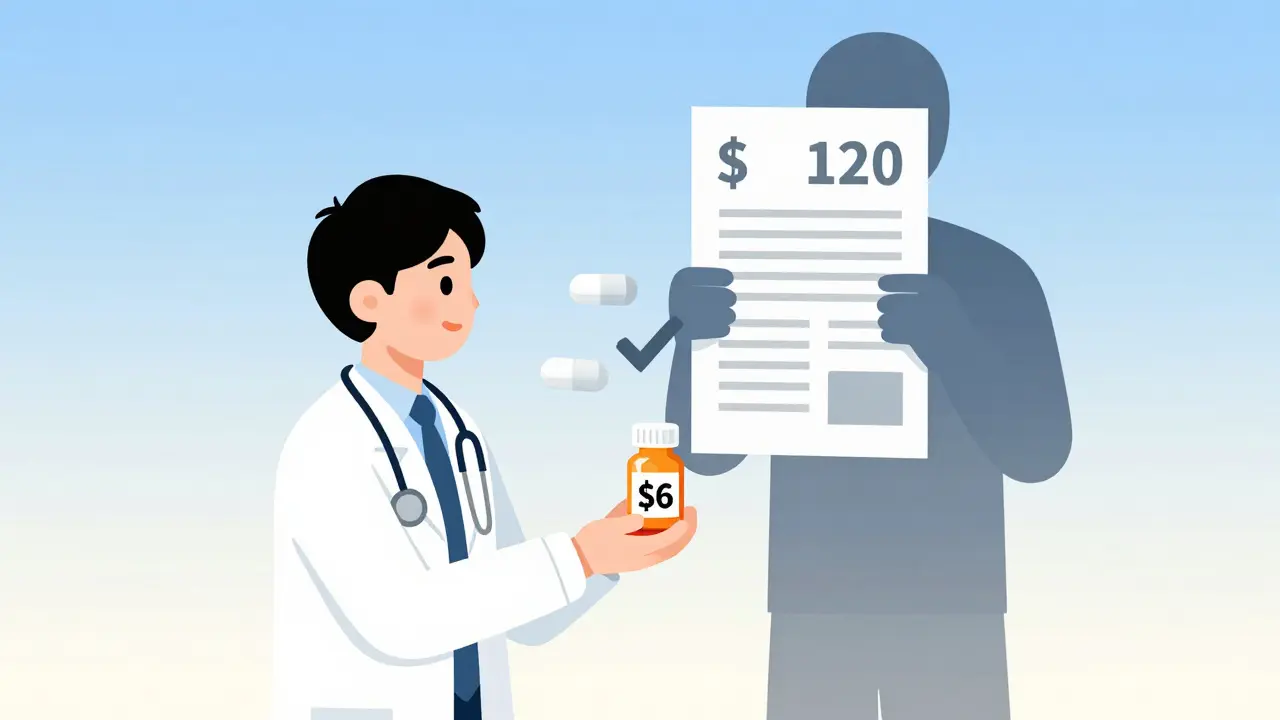

Sometimes, the best generic isn’t even the same drug. It’s a different one in the same class. The JAMA study found that switching from a high-cost generic to a lower-cost therapeutic alternative saved 88% in some cases. That’s not just substitution - that’s strategic replacement. For example: instead of prescribing a $120 generic for hypertension that’s been on the market for years, a clinician might switch to a $6 generic that’s equally effective. The patient gets the same outcome. The system saves $114 per prescription. Multiply that by 10,000 patients, and you’re talking $1.14 million saved in one year. This is where CEA shines. It doesn’t just compare brand vs. generic. It compares all options - brand, generic, alternative generic, alternative drug - and picks the one that delivers the most health for the least cost.

Written by Felix Greendale

View all posts by: Felix Greendale