Imagine eating a salad from a restaurant, then two weeks later you’re sick with fever, nausea, and yellow eyes. You didn’t travel. You didn’t drink bad water. You just had a sandwich. That’s how hepatitis A works - quiet, sneaky, and spread through food most people assume is safe.

How Hepatitis A Moves Through Food

The Virus That Doesn’t Care About Cleanliness

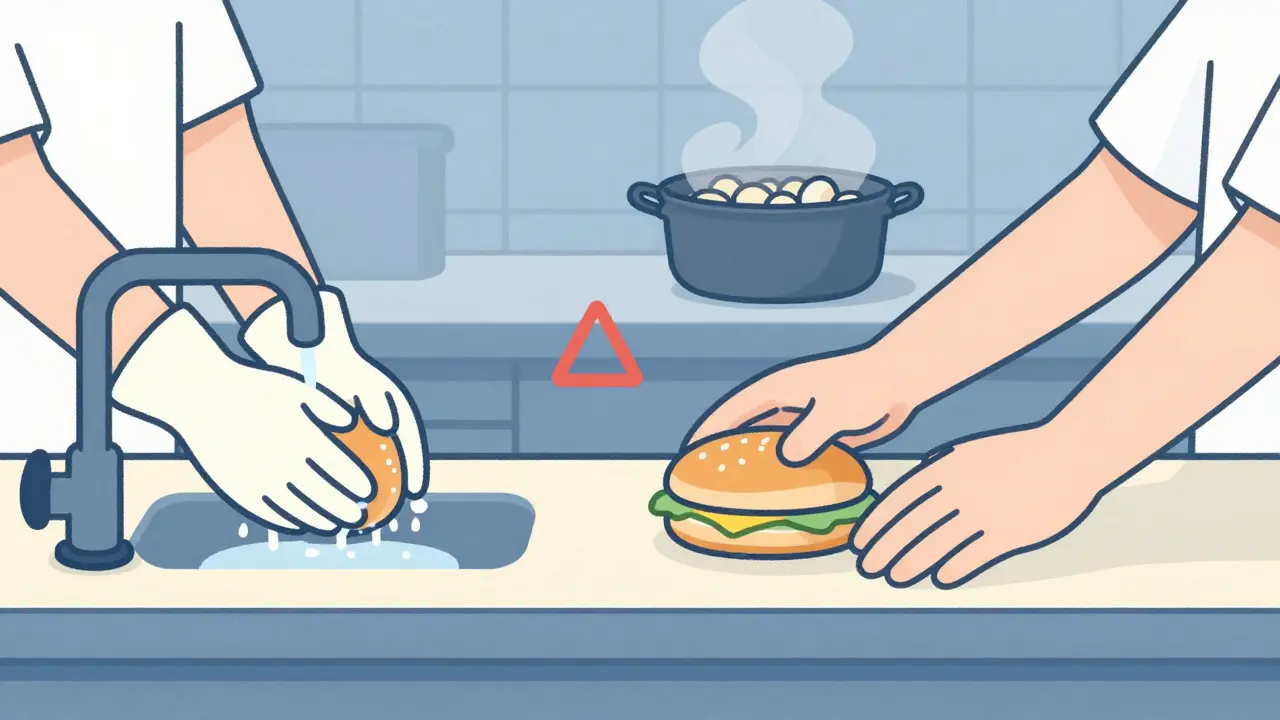

Hepatitis A isn’t like the flu. It doesn’t need coughs or sneezes to spread. It survives on surfaces for weeks. It laughs at cold temperatures. It can live in frozen shrimp for years. All it needs is a few hundred virus particles - less than a speck of dust - to make someone sick.The main route? Fecal matter on someone’s hands. A food worker uses the bathroom, doesn’t wash properly, then touches lettuce, sushi rice, or a sandwich bun. That’s it. No visible dirt. No smell. Just invisible virus particles sticking to food. Studies show nearly 10% of the virus on a contaminated finger can transfer to a piece of lettuce in just 10 seconds of light contact.

Shellfish are a major culprit. They filter seawater, and if that water has sewage runoff, the virus gets trapped inside. Even cooking doesn’t always kill it. The virus can survive at 60°C for a full hour. You need 85°C for at least one minute to destroy it - hotter than most home stoves get. That’s why raw oysters and undercooked clams are high-risk.

Asymptomatic Spread: The Silent Outbreak Engine

Here’s the scary part: up to half of infected adults show no symptoms at all. Kids often feel fine. But they’re still shedding the virus in their poop - for up to three months. And they’re still contagious, even before they feel sick. One infected person working in a kitchen can pass the virus to dozens before anyone notices.Outbreaks often go unnoticed until multiple people get sick weeks later. By then, the contaminated food is gone. The restaurant is cleaned. The worker has moved on. Tracing the source becomes a nightmare.

Who’s at Risk - And Why It’s Not Just Travelers

You don’t need to visit a developing country to catch hepatitis A. In the U.S., most cases now come from local foodborne outbreaks. The CDC says 3-5% of cases are food-related in normal times. But during outbreaks, that jumps to 25%.High-risk settings:

- Restaurants with poor hand hygiene - especially those serving raw or ready-to-eat food

- Food trucks and pop-up vendors with limited handwashing stations

- Places with high staff turnover - fast food, seasonal farms, holiday kitchens

- Communal kitchens where multiple people handle food without gloves

It’s not about where you eat - it’s about who’s preparing your food. Surveys show only 35% of food workers can name hepatitis A symptoms. Only 28% know post-exposure prophylaxis must be given within 14 days. And vaccination rates among food handlers? Below 30% in most places.

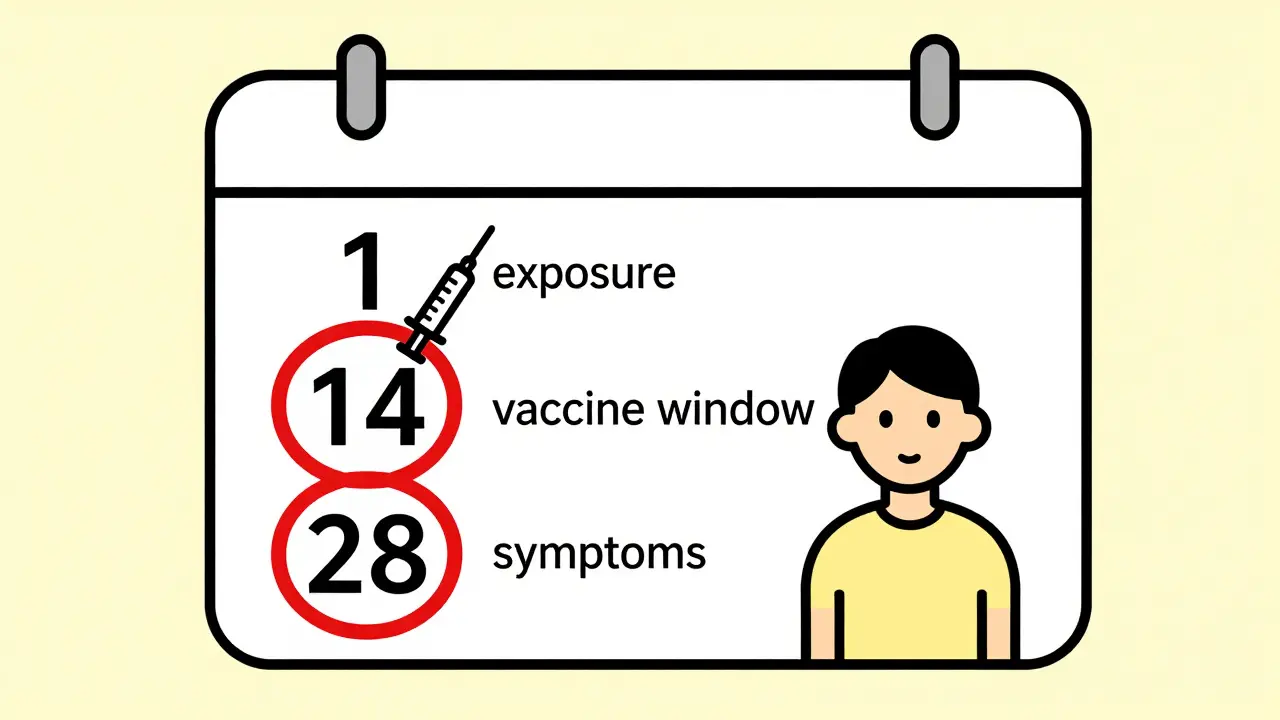

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis: The 14-Day Window

If you find out you ate food handled by someone who later tested positive for hepatitis A, you have 14 days to act. After that, the vaccine won’t stop the infection.There are two options:

- Hepatitis A vaccine - one shot, protects you for at least 25 years. Recommended for people aged 1 to 40. Costs $50-$75.

- Immune globulin (IG) - a shot of antibodies that gives immediate, short-term protection. Lasts 2-5 months. Costs $150-$300. Used for kids under 1, adults over 40, or people with liver disease.

Both work if given within two weeks of exposure. But here’s what most people don’t realize: getting the shot doesn’t mean you’re instantly safe. You still need to avoid touching food for the next six weeks. You can still spread the virus if you’re already infected but not showing symptoms yet.

That’s why handwashing matters more than ever. Soap and water for 20 seconds cuts transmission risk by 70%. Hand sanitizer? Useless against hepatitis A. The virus has no envelope. Alcohol doesn’t touch it.

What Happens After Exposure - Beyond the Shot

If you’re exposed and get the vaccine or IG, you’re protected from getting sick. But if you’re already infected - and don’t know it - you’re still contagious.That’s why food workers who are exposed must follow strict rules:

- Don’t handle food for six weeks

- Wash hands after every bathroom break - even if you feel fine

- Report exposure to your employer immediately

- Wait at least 7 days after jaundice appears before returning to work - or 14 days after symptoms start, depending on your state

California requires 14 days off. Iowa says 7 days after jaundice. There’s no national standard. That’s a problem. A worker who moves from one state to another might think they’re cleared - but they’re still shedding the virus.

Why Vaccination Isn’t Enough - And What Needs to Change

The hepatitis A vaccine is one of the most effective tools we have. But it’s not being used where it’s needed most.As of 2024, 14 U.S. states require food handlers to be vaccinated. That’s up from just six in 2020. California’s mandate since 2022 prevented 120 infections and saved $1.2 million in outbreak costs.

But in most places, it’s still optional. And when it’s optional, only the most responsible workers get vaccinated. The ones with high turnover - the temporary workers, the immigrants, the part-timers - rarely get access. A 2025 study found only 7% of seasonal food workers are vaccinated.

Here’s what works:

- Offering free vaccines at work - increases uptake by 38% when paired with a $50 bonus

- Training with hands-on demos - improves hygiene compliance by 65%

- Installing extra handwashing sinks - required by law (1 per 15 employees), but 22% of inspected places fail

- Testing wastewater in restaurants - new pilot programs detect the virus before anyone gets sick

One restaurant chain in Washington cut outbreaks by 80% after mandating gloves for all ready-to-eat food and requiring vaccination. The cost? $12,000 a year. The savings? Over $500,000 in avoided investigations and lost sales.

What You Can Do - Even If You’re Not a Food Worker

You don’t need to wait for an outbreak to protect yourself.- Get vaccinated if you haven’t already. One shot, lifelong protection.

- Wash your hands thoroughly before eating - even if you’re just grabbing a snack.

- Ask restaurants if they use gloves or utensils for ready-to-eat food. If they don’t, speak up.

- If you’re exposed, act fast. Call your doctor or local health department within 14 days.

- Don’t rely on hand sanitizer. Soap and water are the only thing that works.

It’s not about fear. It’s about awareness. Hepatitis A isn’t going away. But it’s preventable. The tools exist. The science is clear. What’s missing is the will to use them - in kitchens, in clinics, and in our own hands.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you get hepatitis A from cooked food?

Yes - if the food was contaminated before cooking and wasn’t heated to at least 85°C for one minute. Most home cooking doesn’t reach that temperature evenly. Shellfish, salads, and sandwiches are especially risky if handled by an infected person.

How long after exposure do symptoms appear?

Symptoms usually show up 28 days after exposure, but the range is 15 to 50 days. That’s why outbreaks are hard to trace - people don’t connect their illness to a meal from three weeks ago.

Is hepatitis A vaccine safe for pregnant women?

Yes. The hepatitis A vaccine is an inactivated (killed) virus vaccine and is considered safe during pregnancy. Immune globulin is also safe and often preferred for pregnant women over 40 or with liver conditions.

Can you get hepatitis A more than once?

No. Once you recover from hepatitis A, your body develops lifelong immunity. The vaccine also provides long-term protection - at least 25 years, likely for life.

Why doesn’t hand sanitizer work against hepatitis A?

Hepatitis A is a non-enveloped virus, meaning it has a tough protein shell. Alcohol-based sanitizers can’t break through it. Only soap, water, and scrubbing for 20 seconds physically remove the virus from skin.

What should a restaurant do if a worker tests positive?

The worker must stop working immediately. The health department should be notified. All staff exposed in the past two weeks should be offered post-exposure prophylaxis. Surfaces must be cleaned with bleach-based disinfectants. Anyone who ate there in the last 14 days should be contacted and advised to get vaccinated if they haven’t.

Written by Felix Greendale

View all posts by: Felix Greendale