Athletic Hydration Calculator

Calculate Your Sweat Rate

Knowing your sweat rate helps you plan proper fluid replacement to avoid performance decline due to dehydration.

Your Results

Quick Takeaways

- Even a 2% body‑water loss can shave seconds off a sprint and reduce endurance by up to 15%.

- Thirst ramps up because of rising core temperature, sodium loss, and a drop in blood volume.

- Measuring sweat rate lets you calculate personal fluid‑replacement needs.

- Smart hydration tactics-pre‑drink, sip during, and replace electrolytes-keep performance steady.

- Ignoring early thirst signs leads to muscle fatigue, slower heart output, and higher injury risk.

When a runner feels a dry mouth creeping in midway, dehydration is the physiological state where fluid loss outpaces intake, disrupting normal body functions is already kicking in. That simple sensation can be a warning bell for a cascade of performance‑crippling effects.

What Exactly Is Thirst and How Does It Relate to dehydration?

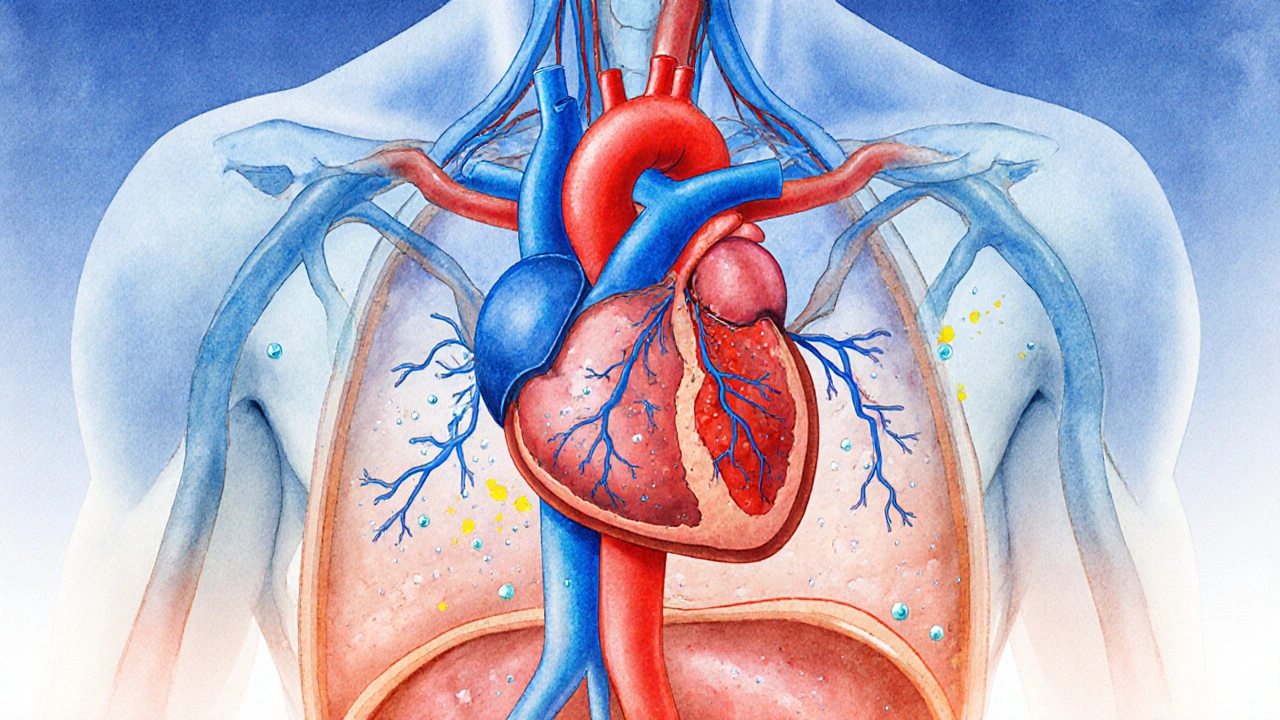

Thirst is the body’s built‑in alarm system. It’s triggered when blood osmolarity rises or blood volume drops, signaling the brain’s hypothalamus to push you toward fluids. Athletic performance refers to the ability to sustain speed, power, and endurance during sport or training is tightly linked to that fluid balance because every muscle contraction, heartbeat, and sweat drop needs water to work efficiently.

How Fluid Loss Messes With Your Body’s Core Systems

When you sweat, you lose not just water but also electrolytes-mainly sodium and potassium. The loss creates three critical shifts:

- Fluid balance the equilibrium between water inside cells and in the bloodstream tilts toward dehydration, shrinking blood volume.

- Core temperature the internal body temperature that rises with exertion climbs faster because evaporative cooling is reduced.

- Electrolyte concentration the level of charged minerals that regulate nerve and muscle function spikes, impairing signal transmission.

These shifts hit cardiovascular output the amount of blood the heart pumps each minute. With less blood circulating, the heart must beat faster to deliver oxygen, raising perceived effort. Muscles receive less oxygen and nutrients, leading to early muscle fatigue the decline in force‑generating capacity after sustained activity. The end result? Slower times, reduced power, and a higher chance of cramping.

Recognizing the Stages of Thirst‑Driven Performance Decline

Performance loss isn’t an all‑or‑nothing switch; it progresses in stages. The table below lines up typical thirst levels with physiological effects and expected performance drops.

| Thirst Level | Body Water Loss | Key Effects | Estimated Performance Hit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 0‑1% | Stable blood volume, normal heart rate | 0‑2% |

| Early Thirst | 1‑2% | Increased heart rate, slight rise in core temperature | 2‑5% |

| Moderate Thirst | 2‑4% | Reduced plasma volume, electrolyte imbalance, noticeable fatigue | 5‑15% |

| Severe Thirst | 4‑6%+ | Sharp drop in stroke volume, dizziness, heat‑related illness risk | 15%+ |

Notice how the performance hit accelerates once you cross the 2% water‑loss threshold? That’s the sweet spot where most athletes start to feel a real drag.

Calculating Your Personal Sweat Rate

One of the most reliable ways to stay ahead of thirst is to know how much you sweat. Here’s a quick field method:

- Weigh yourself nude (or in minimal clothing) right before a training session.

- Train at your typical intensity for 60 minutes.

- Weigh yourself again, dry off, and note the post‑exercise weight.

- Subtract post‑weight from pre‑weight; each kilogram equals roughly 1liter of fluid lost.

- Add any fluid you drank during the session (in liters) to the loss amount to get total sweat volume.

- Divide by the session duration to get liters per hour.

For instance, a 70‑kg cyclist who drops from 70.0kg to 69.2kg while sipping 0.5L of water loses 0.8L of sweat, or about 0.8L/hour. That data tells you exactly how much to replace before the next ride.

Hydration Strategies That Keep Performance on Track

Now that you know the numbers, apply them with smart tactics:

- Pre‑hydrate: Drink 5‑7mL of fluid per kilogram of body weight 2‑3hours before the event. For a 68‑kg runner, that’s about 340‑480mL of water or a sports drink.

- During‑exercise sipping: Aim for 150‑250mL every 15‑20minutes. If your sweat rate is high (>1L/hour), increase to 300mL.

- Electrolyte replacement: Choose drinks that supply 460‑720mg of sodium per liter. This mirrors average sodium loss (≈500mg/L) and helps maintain nerve signaling.

- Post‑exercise recovery: Replenish 150% of fluid lost within 2hours. Use a 3:1 water‑to‑electrolyte mix to speed cellular re‑hydration.

- Environmental tweaks: In hot or humid conditions, wear breathable fabrics, and schedule training during cooler periods when possible.

Notice the balance: pure water quenches thirst, but without salts you risk hyponatremia-another performance killer.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even seasoned athletes stumble over hydration basics. Here are the most frequent mistakes and fixes:

- Relying solely on thirst. By the time you feel thirsty, you’re already ~1‑2% dehydrated. Use scheduled sipping instead.

- Over‑drinking low‑electrolyte fluids. Swamping the system with plain water dilutes sodium, leading to cramps. Pair water with a pinch of salt or a balanced sports drink.

- Ignoring individual variation. Sweat rates differ by genetics, acclimatization, and clothing. Track your own data instead of copying generic recommendations.

- Skipping pre‑hydration on “easy” days. Even low‑intensity sessions cause fluid loss over time. A light pre‑drink maintains baseline balance.

- Neglecting post‑exercise rehydration. The body continues to lose fluid via urine for hours after training. Weigh again 30minutes after finishing to gauge remaining deficit.

Addressing these points keeps you from the performance dip that most athletes attribute to “just feeling tired.” In reality, it’s often dehydration in disguise.

Bottom‑Line Checklist for Athletes

- Measure your sweat rate at least once per season.

- Carry a fluid bottle with a known sodium concentration.

- Pre‑hydrate 2‑3hours before events; sip every 15‑20minutes during.

- Replace 150% of lost fluid within two hours post‑exercise.

- Adjust intake for heat, humidity, altitude, and clothing.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much water should I drink during a one‑hour run?

Aim for 150‑250mL every 15‑20minutes. If you know you sweat heavily (more than 1L per hour), bump the intake to about 300mL per interval.

Can I rely on sports drinks alone for hydration?

Sports drinks are great for replacing both fluid and electrolytes, especially when you lose >500mL per hour. However, for shorter or low‑intensity sessions, plain water is fine; just watch your sodium intake.

What signs tell me I’m moving into moderate dehydration?

Typical cues include a dry mouth, a noticeable increase in heart rate, reduced urine output, and a feeling of heaviness in the legs. A body‑weight drop of 2‑4% after exercise also flags this stage.

Is it possible to over‑hydrate?

Yes. Drinking excessive plain water without electrolytes can dilute blood sodium, causing hyponatremia. Symptoms include nausea, headache, and in extreme cases, seizures. Balance fluid with salt, especially on long events.

How does altitude affect thirst and performance?

Higher altitude leads to faster breathing and greater fluid loss through respiration. Combine that with lower humidity, and you’ll feel thirst sooner. Increase fluid intake by 10‑20% and add a pinch of extra salt to compensate.

Written by Felix Greendale

View all posts by: Felix Greendale