Every year, thousands of people in the UK and around the world get the wrong medicine-not because they asked for it, not because a doctor made a careless mistake, but because two drugs look or sound too much alike. This isn’t rare. It’s one of the most common causes of preventable harm in hospitals and pharmacies. And it’s happening mostly with generic drugs.

What Are Look-Alike, Sound-Alike (LASA) Drugs?

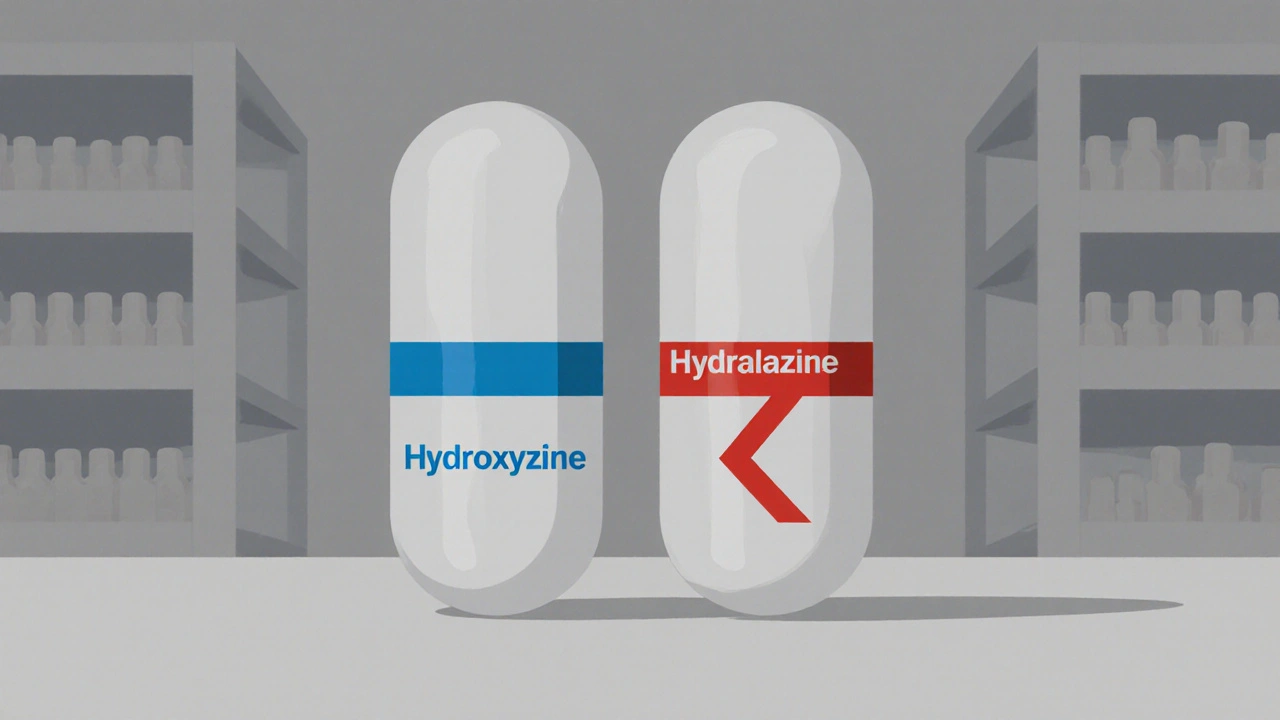

Look-alike, sound-alike (LASA) drugs are medications that are confusing because their names or packaging are too similar. You might see hydroxyzine and hydralazine on a prescription and think they’re the same. They’re not. One treats anxiety. The other lowers blood pressure. Mix them up, and you could cause a dangerous drop in blood pressure-or miss the treatment a patient actually needs.

Sound-alike pairs work the same way. Dopamine and dobutamine sound almost identical when spoken over a noisy intercom in an ICU. One boosts heart function. The other is used for shock. Give the wrong one, and you could kill someone.

These aren’t just spelling errors. They’re systemic failures. Generic drugs make up over 80% of all prescriptions in the UK. But unlike brand-name drugs, generics come from dozens of manufacturers. Each one uses slightly different pill shapes, colours, or labels. That means two versions of the same drug might look totally different-but two different drugs from different makers might end up looking almost identical.

Why Generics Are the Main Culprit

Brand-name drugs have strong visual identities. You know Lipitor by its blue pill. You know Valtrex by its distinctive packaging. But generic versions? They’re often white, oval, and stamped with a code only a pharmacist can read. And when multiple companies make the same generic, the pills can look nearly identical-even if they treat completely different conditions.

Take valacyclovir and valganciclovir. Both start with "val". Both are used for viral infections in immune-compromised patients. But one treats herpes. The other fights CMV, a deadly virus in transplant patients. In 2010, a patient got the wrong one. They ended up with organ rejection. The names were too close. The packaging? Almost the same.

It’s not just names. It’s the way they’re stored. In busy pharmacies, bottles of atenolol (a beta-blocker) and albuterol (an asthma inhaler) might sit side-by-side on the same shelf. One slows your heart. The other speeds it up. A quick grab-and you’ve swapped life-saving medicine for something that could trigger a heart attack.

The Real Cost: Lives, Not Just Money

Medication errors cost the NHS millions. But the real cost is measured in lives.

Between July 2018 and June 2019, the UK’s National Reporting and Learning System recorded over 206,000 medication incidents. Of those, 66 people died. Another 159 suffered severe harm-like strokes, organ failure, or permanent nerve damage. A quarter of those incidents were linked to LASA drugs.

It’s not just hospitals. Community pharmacies see it every week. A 2021 survey found that 78% of pharmacists had encountered a LASA error at least once a month. One in three said they’d had a near-miss-where the error was caught just in time.

And it’s worse for children. While fewer errors happen in paediatric settings, when they do, the consequences are often deadly. A child given the wrong dose of a LASA drug can suffer brain damage or cardiac arrest within minutes.

What’s Being Done-And Why It’s Not Enough

There are solutions. But they’re not being used everywhere.

Tall man lettering is one of the oldest tricks. Instead of writing "prednisone" and "prednisolone", you write "predniSONE" and "predniSOLONE". The capital letters highlight the difference. A 2020 study showed this cut errors by 67% in 12 hospitals.

Physical separation works too. Keeping high-risk pairs like hydralazine and hydroxyzine on different shelves, or even in different cabinets, stops accidental grabs. Many UK hospitals now use colour-coded labels or warning stickers on high-risk drugs.

Barcode scanning with clinical alerts is another game-changer. When a nurse scans a drug, the system checks: "Is this the right drug for this patient?" If it’s a LASA match, it flashes a warning. One hospital system cut LASA errors by 45% using this method.

And now, AI is stepping in. A 2023 study found that AI tools embedded in electronic health records caught 98.7% of potential LASA errors-with only 1.3% false alarms. That’s huge. But only a few hospitals in the UK have these systems. Most still rely on human memory and tired pharmacists working 12-hour shifts.

What You Can Do-Even If You’re Not a Doctor

You don’t need a medical degree to help prevent these errors. Here’s what you can do:

- Ask for the generic name. If your prescription says "atenolol 50mg", ask the pharmacist: "Is this the same as the one I used before?" If it looks different, question it.

- Check the pill. Compare the colour, shape, and imprint code on the pill to the last one you took. If it’s changed, ask why.

- Know the purpose. Don’t just take the pill because it’s in the bottle. Ask: "What is this for?" If the answer doesn’t match your condition, stop and double-check.

- Speak up in hospitals. If you hear a nurse say "dobutamine" but you’re on dopamine, say something. You’re the last line of defence.

And if you’re a caregiver for an elderly or disabled person, keep a written list of all their medications-names, doses, and why they’re taking them. Bring it to every appointment. Pharmacists and doctors appreciate it. And it might save a life.

The Bigger Picture: It’s Not About Blame

Dr. David Bates from Harvard says it best: LASA errors aren’t caused by bad people. They’re caused by bad systems.

Pharmacists aren’t careless. Nurses aren’t lazy. But when you have 300 drugs on a screen, and 20 of them look like twins, mistakes happen. No amount of training can fix that.

What we need are rules. Standardised packaging. Mandatory name checks for all new generics. AI alerts built into every pharmacy system. And global standards so that a pill in Brighton looks different from a similar pill in Manchester-or Paris or New York.

The WHO’s "Medication Without Harm" campaign wants to cut severe medication errors by 50% by 2025. That’s possible. But only if we treat LASA errors like the public health crisis they are-not just a "pharmacy problem".

Right now, the FDA in the US rejected 34 drug names in 2021 just because they were too similar to existing ones. The EMA in Europe now requires name-similarity checks for every new drug. The UK? We’re still catching up.

What Comes Next?

The future of medication safety isn’t about better training. It’s about better design.

Imagine a world where:

- Every generic drug has a unique pill shape based on its class-not just what the manufacturer prefers.

- All LASA pairs are automatically flagged in every EHR, pharmacy system, and prescription app.

- Pharmacies use smart shelves that won’t let you pick two similar drugs at once.

- Patients get a QR code on their prescription that links to a video explaining the drug’s purpose and what to watch for.

We’re not far from this. The tech exists. The data proves it works. What’s missing is the will to make it universal.

Until then, stay alert. Ask questions. Trust your gut. If something looks wrong-it probably is. And in medicine, that one question could be the difference between a routine refill and a tragedy.

Written by Felix Greendale

View all posts by: Felix Greendale