Imagine waking up one day and noticing your walk has changed. Your feet feel stuck to the floor, like you’re walking through deep snow. You forget where you put your keys. You start having accidents you never had before. At first, you blame aging. Maybe your doctor says it’s just getting older. But what if this isn’t normal aging at all? What if it’s something treatable - something that can be fixed with surgery?

This is normal pressure hydrocephalus, or NPH. It’s not rare. In fact, up to 5.9% of nursing home residents have it. Yet most people - even doctors - miss it. And that’s a problem, because NPH is one of the few types of dementia that can be reversed.

What Exactly Is Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus?

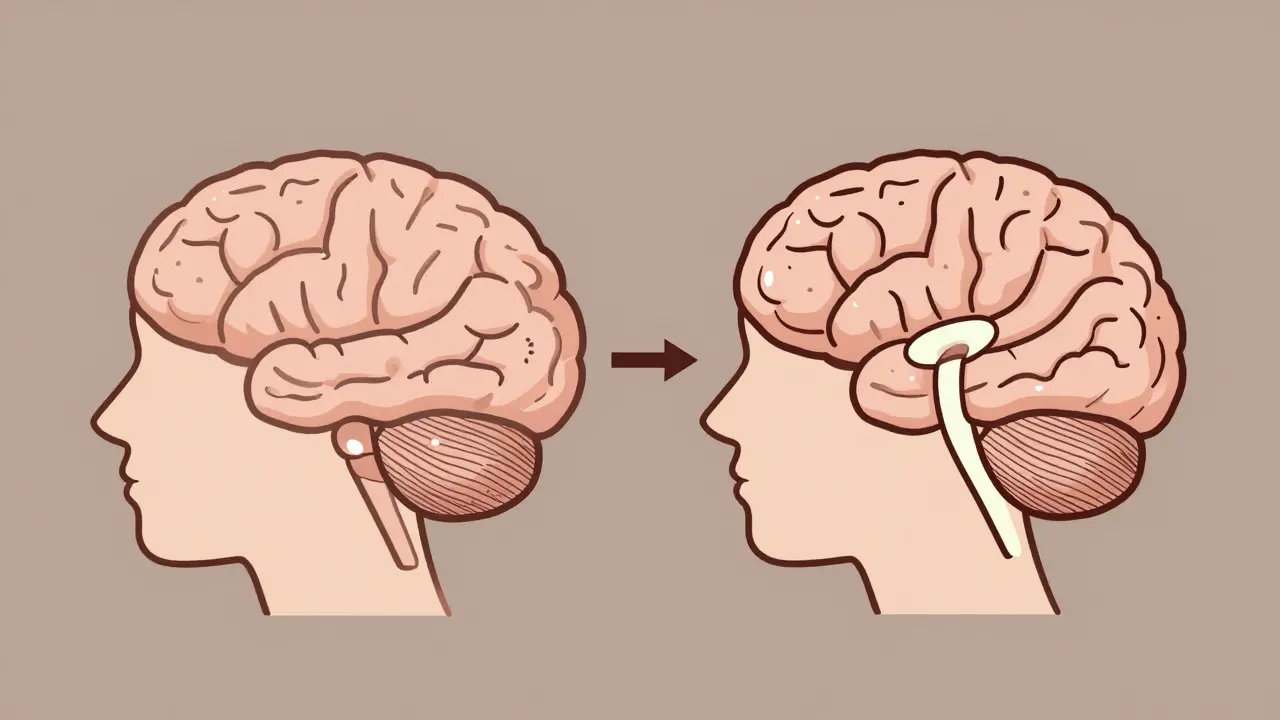

NPH happens when too much cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) builds up in the brain’s ventricles. These are natural spaces that normally hold fluid to cushion the brain. In NPH, the fluid doesn’t drain properly. The pressure stays normal - that’s why it’s called normal pressure hydrocephalus. But the ventricles still swell, squeezing nearby brain tissue.

This condition was first clearly described in 1965 by two neurosurgeons, Salomón Hakim and Raymond Adams. Since then, we’ve learned that it mostly affects people over 60. It’s not caused by a tumor or stroke. In 80-90% of cases, there’s no clear reason why the fluid stops flowing right. That’s called idiopathic NPH. The rest are linked to past head injuries, brain infections, or bleeding in the brain.

What makes NPH tricky is that it looks like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or just old age. But the symptoms are different - and so is the treatment.

The Three Signs: Gait, Cognition, and Bladder Control

NPH has a classic trio of symptoms, but not everyone gets all three. And they don’t always show up at the same time.

Gait disturbance is the most common - and the most telling. It’s not just slow walking. It’s a specific kind: wide-based, shuffling steps, as if your feet are glued to the ground. People often say they feel like they’re walking on ice. You can’t turn quickly. You might freeze mid-step. In studies, nearly 100% of confirmed NPH patients have this symptom. It’s so distinctive that neurologists call it a “magnetic gait.”

Cognitive changes come next. It’s not memory loss like Alzheimer’s. It’s more about slowing down. You forget why you walked into a room. You struggle to plan your day. You lose focus. You take longer to respond in conversation. Neuropsychological tests show problems with executive function - the part of your brain that handles decision-making, organization, and attention. This isn’t just being forgetful. It’s a brain-wide slowdown.

Urinary incontinence is the last to appear - and often the most embarrassing. It doesn’t start suddenly. It creeps in. You feel urgency, then accidents. You might start wearing pads. Many patients delay telling their doctor because they’re ashamed. But this symptom is a red flag. If you have gait trouble and memory issues, and now you’re having bladder problems, NPH should be on the table.

Only about 30% of patients have all three symptoms together. That’s why so many cases get missed. If you only have one or two, it’s easy to chalk it up to something else.

How Is NPH Diagnosed?

Diagnosing NPH isn’t just about looking at symptoms. You need proof.

First, doctors order brain imaging - usually an MRI or CT scan. They measure something called the Evan’s index. If it’s above 0.3, the ventricles are enlarged. They also look for signs of fluid buildup around the ventricles, called periventricular hyperintensities. These are telltale markers.

But imaging alone isn’t enough. You need to test how the brain responds to removing fluid. That’s where the CSF tap test comes in.

In this test, a doctor drains 30-50 milliliters of spinal fluid with a needle - same as a lumbar puncture. Then, they measure your walking speed, balance, and mental clarity before and after. If you walk 10% faster or score better on a memory test, that’s a strong sign you’ll respond to a shunt. Studies show this test predicts shunt success with 82% accuracy.

Some centers use a more advanced version called external lumbar drainage, where a catheter stays in for a few days to slowly remove fluid. This gives a longer window to see changes. But the tap test is still the standard because it’s simpler, safer, and widely available.

Doctors also rule out other causes. Parkinson’s causes tremors and stiffness. Alzheimer’s hits memory first. Vascular dementia comes after strokes. NPH? Gait comes first. And it’s reversible.

Shunt Surgery: The Treatment That Works

If the tap test shows improvement, the next step is surgery - a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt.

This isn’t brain surgery in the scary sense. It’s a routine procedure. Two thin tubes are placed: one goes from the brain’s ventricle, down the neck and chest, into the abdomen. The other connects to a small valve that controls how fast fluid flows. The valve is set to open at a pressure between 50 and 200 mm H₂O - low enough to drain excess fluid but not so low that it drains too much.

The surgery takes about an hour. Most people go home in 2-3 days. Recovery takes 6-12 weeks. But the results? Sometimes, they’re immediate.

One 72-year-old man posted online: “After my shunt, my 10-meter walk went from 28 seconds to 12 seconds - in 48 hours.” He hadn’t walked normally in over a year. He got his independence back.

Studies show 70-90% of properly selected patients improve after shunt placement. Gait improves in 76% of cases. Cognitive function gets better in 62%. Bladder control returns for 58%. And 89% of patients say they’re glad they had the surgery.

But it’s not magic. Not everyone benefits. About 20-30% of shunts don’t help - even if the tap test looked good. Why? Sometimes, the brain has already changed too much. Sometimes, there’s another condition hiding in the background - like early Alzheimer’s mixed with NPH. That happens in 25-30% of cases.

What Can Go Wrong?

Shunts work - but they’re mechanical devices. And like any machine, they can break.

The biggest risks are infection (about 8.5% of cases), shunt malfunction (15.3% within two years), and bleeding around the brain (5.7%). These are more common in older patients, especially those over 80.

Shunts can get clogged. They can drain too much fluid, causing the brain to sink and pull on blood vessels - leading to headaches or even a subdural hematoma. That’s why follow-up is critical. Patients need check-ups at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after surgery. Sometimes, the valve pressure needs adjusting.

One woman shared on a patient forum: “I had a good tap test, but my shunt didn’t help my memory. I ended up with chronic headaches and had to get the valve reprogrammed.”

That’s why patient selection matters. You don’t just operate on anyone with gait trouble. You need clear evidence from testing. Delaying surgery beyond 12 months from symptom onset can cut your chances of success by 30%.

Why Is NPH So Often Missed?

Because it looks like something else.

Most people assume memory loss and slow walking in older adults are just part of aging. Doctors don’t always think of NPH unless they specialize in movement disorders or dementia. The average time from first symptom to diagnosis? 14.3 months. That’s over a year of unnecessary decline.

Insurance doesn’t always help either. In 37% of cases, insurers deny coverage for the CSF tap test or lumbar drainage - even though these are proven diagnostic tools. That delays care and pushes patients toward more expensive, less effective treatments like Alzheimer’s medications.

And here’s the kicker: NPH is cheaper to treat than Alzheimer’s. A shunt costs about $28,000. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s? They cost thousands per year - and only help 35% of patients. Shunts help 78%.

What’s New in NPH Treatment?

There’s real progress happening.

In 2022, the FDA approved a new device called the Radionics® CSF Dynamics Analyzer. It measures how well your brain drains fluid - something that used to require guesswork. Now, doctors can see if your CSF outflow resistance is low, which predicts shunt success with 89% accuracy.

There’s also an app now - the iNPH Diagnostic Calculator. You plug in 12 symptoms and test results, and it tells you your chance of responding to a shunt. It’s 85% accurate.

And researchers are working on a blood test. Three clinical trials are testing biomarkers in spinal fluid that could one day diagnose NPH without a tap test. Preliminary results show 92% sensitivity. If this works, it could change everything.

What Should You Do If You Suspect NPH?

If you or a loved one has:

- Shuffling, unsteady walking that’s getting worse

- Slowed thinking, trouble planning, or forgetfulness that doesn’t match typical memory loss

- Bladder control issues that started after walking problems

- then ask for an evaluation for NPH.

Start with your primary doctor. Ask for a referral to a neurologist who specializes in movement disorders or dementia. Insist on brain imaging and a CSF tap test. Don’t accept “it’s just aging.”

NPH isn’t common, but it’s treatable. And the window to fix it is narrow. The sooner you act, the better the chance of getting your life back.

Can normal pressure hydrocephalus be cured?

NPH can’t be completely cured, but its symptoms can be reversed in most cases with a shunt. Many patients regain their ability to walk, think clearly, and control their bladder. The earlier the treatment, the better the outcome. Long-term studies show that 68% of patients still have improved function 20 years after surgery.

Is NPH the same as Alzheimer’s?

No. Alzheimer’s starts with memory loss and confusion, especially for recent events. NPH starts with walking problems - often before memory issues. The brain changes are different too. Alzheimer’s shows shrinking of the hippocampus; NPH shows enlarged ventricles with normal brain volume. Unlike Alzheimer’s, NPH can be treated surgically with high success rates.

How do I know if I’m a good candidate for a shunt?

You’re a good candidate if you have the classic triad of symptoms, imaging shows enlarged ventricles, and you improve after a CSF tap test. Improvement of at least 10% in walking speed or cognitive score after fluid removal is the key predictor. Patients under 80 with no other major brain diseases have the best outcomes.

What are the risks of shunt surgery?

The main risks are infection (about 8.5%), shunt malfunction (15% within two years), and bleeding around the brain (5.7%). Older patients have higher risks. Shunts can also drain too much fluid, causing headaches or dizziness. Regular follow-ups and valve adjustments can reduce these risks.

How long does recovery take after shunt surgery?

Most people go home within 2-3 days. Walking usually improves within days to weeks. Full recovery - including cognitive and bladder function - takes 6-12 weeks. Some patients report feeling better within 48 hours. But patience is key. The brain needs time to adjust to the new fluid balance.

Can NPH come back after shunt surgery?

The condition doesn’t “come back,” but the shunt can fail. Shunts are mechanical devices and can clog, break, or drain too much or too little fluid. About 32% of patients need at least one revision surgery over time. Regular check-ups help catch problems early. The shunt doesn’t cure the underlying fluid flow issue - it manages it.

Written by Felix Greendale

View all posts by: Felix Greendale