Osteodystrophy Risk Assessment Tool

Select any symptoms you've experienced during pregnancy:

Select any risk factors you have:

Your Risk Assessment

osteodystrophy pregnancy poses unique challenges for both mother and baby, especially when bone metabolism goes off‑track during the nine months of gestation.

Key Takeaways

- Osteodystrophy is a spectrum of bone‑remodeling disorders driven by calcium, phosphate, and hormone imbalances.

- Pregnancy increases calcium demand by up to 30%, raising the risk of bone loss if intake or absorption is insufficient.

- Early symptoms include persistent back pain, height loss, and easy fractures.

- Diagnosis relies on blood tests (calcium, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone) and bone‑density scans.

- Management blends diet, safe supplementation, targeted exercise, and close monitoring; most drugs are avoided until after delivery.

What Is Osteodystrophy?

When a pregnant woman experiences osteodystrophy is a disorder of bone metabolism caused by imbalances in calcium, phosphate, and hormone levels, her bones may become fragile and pain‑prone. The condition includes several subtypes, the most relevant to pregnancy being:

- Pregnancy‑induced osteoporosis - a temporary drop in bone density due to high calcium demand.

- Renal osteodystrophy - bone disease secondary to chronic kidney dysfunction, which can worsen during pregnancy.

Why Pregnancy Changes Bone Health

During pregnancy, the fetus requires about 30g of calcium, primarily for skeletal growth. The mother meets this need through three physiological routes:

- Enhanced intestinal calcium absorption, driven by higher vitamin D levels (specifically calcitriol).

- Mobilisation of calcium from maternal bone stores if dietary intake falls short.

- Renal re‑absorption adjustments mediated by parathyroid hormone (PTH).

If any of these pathways falter-say, due to low dietary calcium, vitamin D deficiency, or pre‑existing kidney disease-the balance tips toward bone loss, setting the stage for osteodystrophy.

Risks for Mother and Baby

Maternal bone loss isn’t just a cosmetic issue; it carries real health consequences:

- Fractures - especially of the vertebrae or ribs, can happen with minimal trauma.

- Post‑partum osteoporosis - bone density may remain low for months after delivery.

- Reduced fetal bone mineralisation - severe maternal deficiency can lead to neonatal rickets.

- Complications for future pregnancies - each episode can erode the skeletal reserve further.

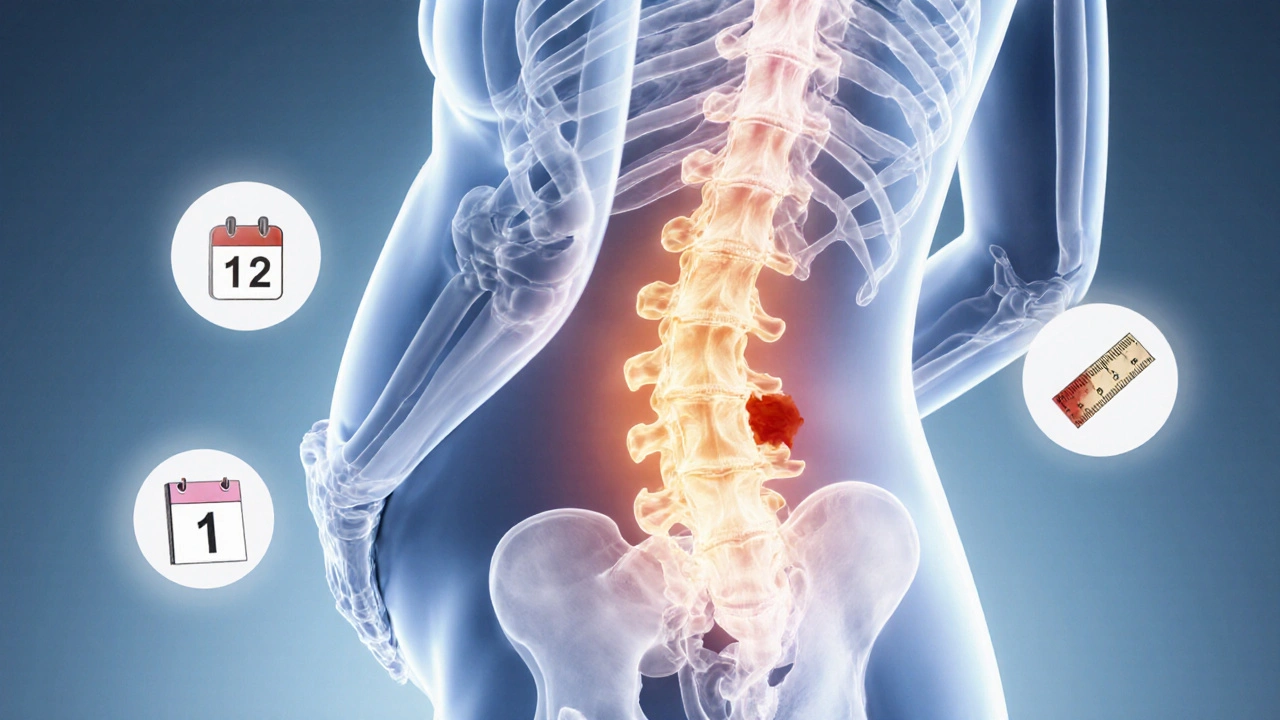

Spotting the Symptoms Early

Unlike common pregnancy aches, osteodystrophy‑related pain is persistent, worsens with activity, and may improve only with rest. Look for:

- Unexplained lower‑back or hip pain lasting more than two weeks.

- Loss of height of more than 1cm over a short period.

- Easy bruising or minor fractures after low‑impact falls.

If any of these appear, bring them up at the next antenatal visit.

How Is Osteodystrophy Diagnosed?

Doctors combine clinical clues with targeted investigations:

- Serum calcium - measured with calcium test. Low or high levels can indicate underlying issues.

- Serum 25‑OH vitamin D - gauges vitamin D status; levels below 20ng/mL suggest deficiency.

- PTH assay - flags secondary hyperparathyroidism, a common driver of bone loss.

- Alkaline phosphatase - often rises in high bone turnover states.

- Dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA) - the gold‑standard for measuring bone density. A T‑score between -1.0 and -2.5 indicates osteopenia; below -2.5 signals osteoporosis.

Management Strategies

Because most medications cross the placenta, the first line of defense is non‑pharmacologic.

| Option | Benefits | Potential Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Calcium | Supports fetal bone formation, improves maternal bone density | Rare gastrointestinal upset if excessive |

| Vitamin D Supplementation | Enhances calcium absorption, reduces secondary hyperparathyroidism | Hypercalcemia if overdosed |

| Weight‑bearing Exercise | Stimulates bone remodeling, improves muscle strength | Risk of injury if improper technique |

| Calcitriol (Active Vitamin D) | Effective for severe deficiency, fast correction | Requires close monitoring; may cause hypercalcemia |

| Bisphosphonates | Powerful anti‑resorptive | Contraindicated in pregnancy; potential fetal skeletal effects |

Below is a deeper dive into each pillar.

1. Optimise Calcium Intake

Guidelines suggest 1,200mg of calcium daily for pregnant women. Good sources include low‑fat dairy, fortified plant milks, leafy greens, and almonds. If dietary intake falls short, a calcium carbonate supplement (up to 500mg twice daily) is safe.

2. Ensure Adequate Vitamin D

Vitamin D status is measured as 25‑OH D. The NICE guidelines recommend 10µg (400IU) of vitamin D daily for all pregnant women, with higher doses (1,000-2,000IU) for those deficient. Vitamin D2 and D3 are interchangeable, but D3 has a slightly better bioavailability.

3. Safe Exercise Routine

Weight‑bearing activities like brisk walking, low‑impact aerobics, and prenatal yoga keep bone turnover balanced. Aim for 150 minutes per week, spread across the week. Avoid high‑impact sports that risk abdominal trauma.

4. Targeted Pharmacologic Options

When labs show severe deficiency or rapid bone loss, clinicians may prescribe:

- Calcitriol (0.25-1µg daily) - the active form of vitamin D, reserved for cases where the mother cannot convert vitamin D efficiently.

- Calcium‑sensing‑receptor agonists - rarely used, only in specialist centers.

Bisphosphonates, denosumab, and teriparatide are avoided until after delivery because they can cross the placenta and affect fetal bone modelling.

5. Monitoring Schedule

Regular follow‑up is crucial. A typical plan looks like:

- Baseline labs and DXA at diagnosis.

- Repeat calcium, vitamin D, and PTH every 4-6 weeks.

- Second DXA scan at 28weeks if rapid loss is suspected.

- Post‑partum reassessment at 6 weeks and again at 6 months.

Special Considerations

Women with pre‑existing chronic kidney disease may develop renal osteodystrophy, a complex form of bone disease driven by phosphate retention and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Management requires a nephrologist‑obstetric team, stricter phosphate control, and possibly calcitriol plus calcium carbonate under close monitoring.

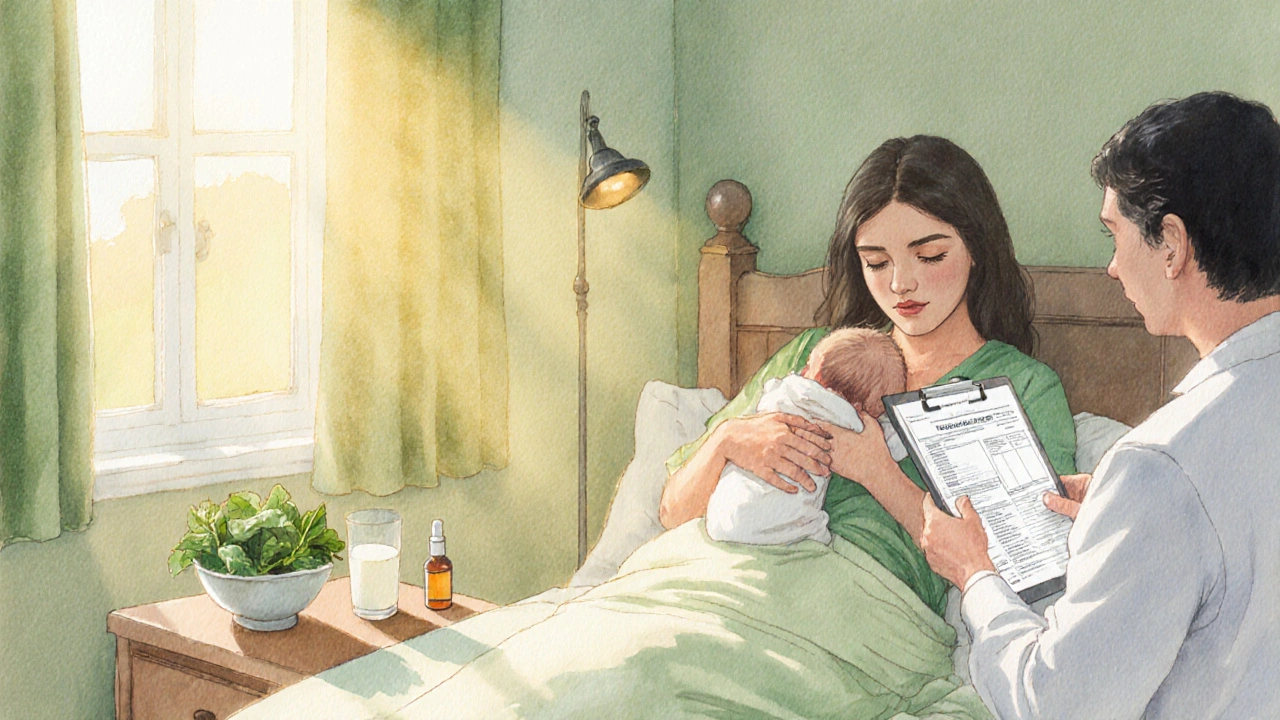

After the Baby Arrives

Once the placenta is delivered, calcium demand drops sharply. This is an ideal window to reassess bone health, taper supplements if levels are adequate, and consider starting anti‑resorptive therapy if osteoporosis persists. Breast‑feeding mothers need continued calcium (1,000mg) and vitamin D (10µg) to protect both themselves and the infant.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get osteodystrophy if I take prenatal vitamins?

Most prenatal vitamins contain the recommended 400IU of vitamin D and 200-300mg of calcium, which covers basic needs. However, if you have risk factors like low BMI, limited sun exposure, or a history of kidney disease, you may still fall short and need additional supplementation.

Is it safe to have a DXA scan during pregnancy?

DXA uses a very low radiation dose (about 1µSv), which is considered safe for pregnancy when medically indicated. The scan is usually performed on the lumbar spine and hip, avoiding the abdomen.

What symptoms should prompt an urgent visit?

Sudden severe back pain, a noticeable loss of height, or any fracture after a minor fall should trigger immediate medical attention. These could signal rapid bone loss or an impending vertebral fracture.

Can bisphosphonates be used after delivery?

Yes. Once breastfeeding is discontinued, bisphosphonates like alendronate can be considered for women with persistent osteoporosis. Treatment should be timed at least 6 months postpartum to allow bone healing from childbirth.

How does renal osteodystrophy differ from pregnancy‑induced osteoporosis?

Renal osteodystrophy stems from chronic kidney dysfunction affecting phosphate and PTH balance, often leading to high‑turnover bone disease. Pregnancy‑induced osteoporosis is usually a low‑turnover, temporary condition driven by calcium deficit. Management of renal osteodystrophy requires nephrology input and stricter control of phosphorus and PTH.

Written by Felix Greendale

View all posts by: Felix Greendale