When your lower back aches after standing too long, or your hamstrings feel tighter than usual, it’s easy to blame it on aging or a bad day at the gym. But if that pain keeps coming back-especially when walking or standing-and doesn’t improve with rest, you might be dealing with something more specific: spondylolisthesis. It’s not just a generic back problem. It’s when one of your spinal bones slips forward over the one below it, usually in the lower back. This isn’t rare. About 6 in every 100 people have it. Many never even know. But for others, it’s a constant source of pain, nerve issues, and uncertainty about what to do next.

What Exactly Is Spondylolisthesis?

Spondylolisthesis comes from Greek: spondylo means vertebra, and olisthesis means to slip. So, it’s literally a slipped vertebra. Most often, it happens between the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) and the first sacral bone (S1). That’s the spot where your lower spine meets your pelvis. It’s under the most stress during daily movement, which is why it’s the most common location.

There are five main types, and knowing which one you have matters for treatment. The most common in adults over 50 is degenerative spondylolisthesis. It’s caused by years of wear and tear-arthritis breaking down the discs and joints that hold your spine in place. About 65% of adult cases fall into this category. In younger people, especially athletes, it’s often isthmic, caused by a small fracture in a part of the bone called the pars interarticularis. Gymnasts, football players, and weightlifters are at higher risk because their sports demand repeated backward bending of the spine.

Other types are rarer. Dysplastic means you were born with a structural flaw in your spine. Pathologic happens when diseases like tumors or osteoporosis weaken the bone. Traumatic is from a sudden injury, like a fall or car crash. Most cases aren’t from trauma. They build up slowly.

Why Does It Hurt? The Symptoms You Can’t Ignore

Here’s the thing: nearly half of people with spondylolisthesis feel nothing at all. You could have a slip and never know unless you get an X-ray for another reason. But when symptoms show up, they’re hard to miss.

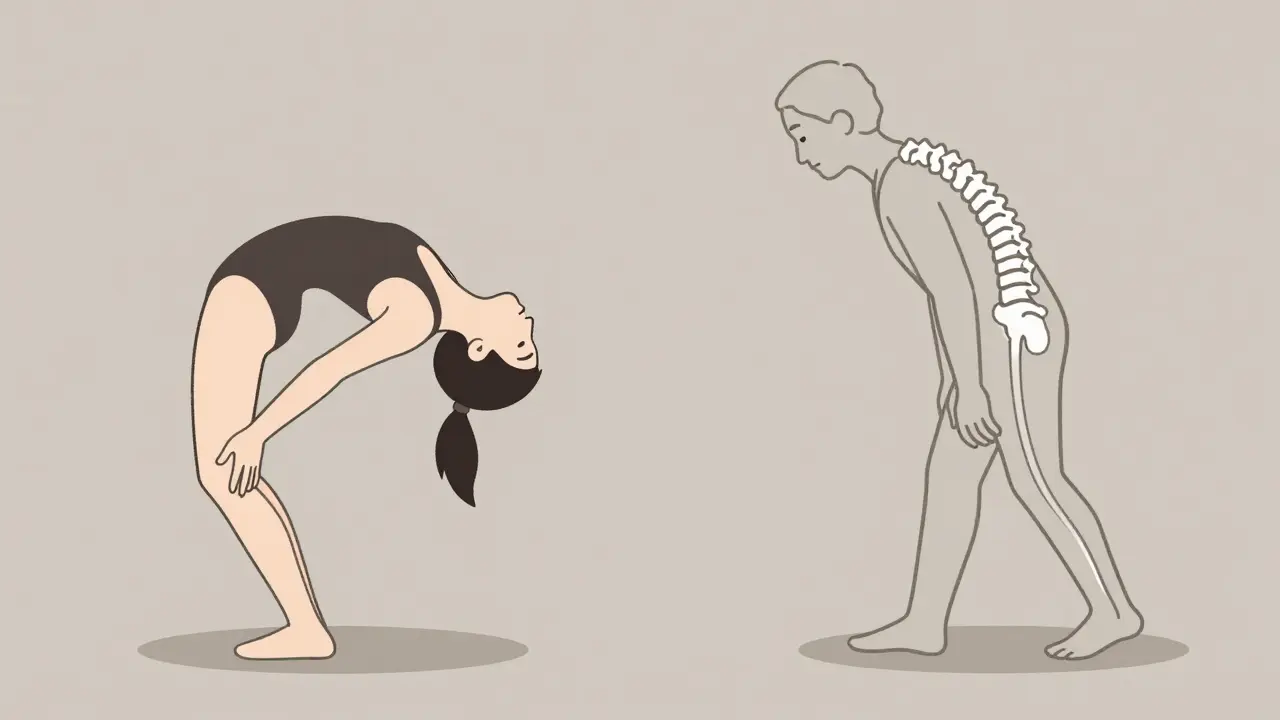

The most common complaint is lower back pain that feels like a deep muscle strain. It gets worse when you stand or walk, and better when you sit or lean forward. That’s because leaning forward opens up the space around your spinal nerves. Eighty-two percent of people with symptoms report this pattern. You might also feel tightness in your hamstrings-around 70% of symptomatic cases do. That’s not just coincidence. The slipped vertebra pulls on the nerves that run down your legs, making your muscles tense up as a protective response.

If the slip is severe (Grade III or IV on the Meyerding scale, meaning more than 50% of the bone has moved forward), you might start feeling tingling, numbness, or weakness in one or both legs. That’s nerve compression. In advanced cases, the spine can start to curve abnormally. You might develop a swayback at first, then later, a rounded upper back (kyphosis) as the upper spine loses support.

Progressive cases can lead to neurogenic claudication-a cramping pain in your legs when walking, forcing you to stop and rest. People with high-grade slips are nearly three times more likely to develop this than those with mild slips.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t guess. They look. The first step is always a standing lateral X-ray. That’s the only way to see how far the bone has slipped. The Meyerding scale grades it from I to IV: Grade I is less than 25% slippage, Grade IV is more than 75%. Most cases are Grade I or II.

If the X-ray shows something, the next step is usually an MRI. That shows the soft tissues: the discs, the nerves, any swelling or inflammation. A CT scan might follow if the doctor needs to see the bone structure in detail-especially if they’re considering surgery. The goal isn’t just to see the slip. It’s to figure out if the nerves are being squeezed and how much damage the spine has taken over time.

One key insight from recent research: the severity of disc degeneration correlates more closely with age than with the degree of slippage. That means two people with the same slip percentage can have very different levels of pain. One might be 70 with worn-out discs and constant pain. The other might be 55 with a similar slip but healthy discs and no symptoms. Treatment isn’t about fixing the slip-it’s about fixing the pain.

Conservative Treatment: What Works Before Surgery

Most people never need surgery. In fact, 80-90% of cases improve with non-invasive methods. The first rule? Stop what hurts. If you’re a runner or a weightlifter, you need to cut back on activities that involve hyperextending your back. That means avoiding heavy deadlifts, gymnastics moves, or anything that arches your spine forcefully.

Physical therapy is the cornerstone. A good program focuses on two things: strengthening your core and stretching your hamstrings. Core muscles act like a natural brace for your spine. Strong abs and glutes reduce the load on the slipped vertebra. Stretching tight hamstrings takes pressure off the lower spine. Most patients see real improvement after 12 to 16 weeks of consistent therapy. But adherence is low-only about 65% stick with it long enough to benefit.

Medications help manage pain. Over-the-counter NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen reduce inflammation. If pain is severe, a doctor might suggest an epidural steroid injection. That’s a shot of cortisone near the affected nerve. It doesn’t fix the slip, but it can calm the inflammation and give you enough relief to start physical therapy.

Bracing is rarely used in adults, but sometimes recommended for teens with isthmic spondylolisthesis to let the fracture heal. For older adults, braces offer little benefit and can weaken muscles if worn too long.

Fusion Surgery: When It’s Time to Consider the Knife

Surgery isn’t a first option. It’s a last resort. Most guidelines say to try 6 to 12 months of conservative care first. But if your pain is disabling, you can’t walk more than a few blocks, or your legs are going numb, it’s time to talk about fusion.

Spinal fusion means joining two vertebrae together so they heal into one solid bone. This stops the slip from getting worse and takes pressure off the nerves. There are three main types:

- Posterolateral fusion (55% of procedures): Bone graft is placed along the back of the spine, and screws or rods hold it in place. It’s the oldest method, but less effective for severe slips.

- Interbody fusion (35% of procedures): This includes PLIF (posterior lumbar interbody fusion) and TLIF (transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion). The damaged disc is removed, and a spacer is inserted between the vertebrae. This restores disc height, opens up the nerve pathways, and gives better stability. Success rates are higher-85% to 92% across all slip grades.

- Minimally invasive fusion (10% of procedures): Smaller incisions, less muscle damage. Recovery is faster, but it’s not for everyone. It works best for Grade I and II slips.

Success isn’t just about the surgery. It’s about preparation. Smokers have more than three times the risk of the bones failing to fuse. Losing weight matters too-if your BMI is over 30, complications rise by 47%. Quitting smoking and getting your weight down before surgery isn’t optional. It’s critical.

What Happens After Surgery?

Recovery isn’t quick. You’ll be restricted from lifting, twisting, or bending for 6 to 8 weeks. Physical therapy starts around 6 to 8 weeks post-op and lasts 3 to 6 months. Full healing can take 12 to 18 months. Most patients report high satisfaction-78% to 85% say their pain is significantly better after two years.

But there’s a catch. About 12% to 15% of patients with high-grade slips need a second surgery. Why? Adjacent segment disease. When you fuse one level, the segments above and below take on more stress. Over time, those discs can wear out too. Studies show 18% to 22% of fusion patients develop new problems in nearby areas within five years.

New Options on the Horizon

Surgery isn’t the only future. In 2022, the FDA approved two new interbody devices designed specifically for spondylolisthesis. Early results show 89% fusion rates at six months-better than older models. Biologics like bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and stem cell therapies are being tested. One 2023 trial found BMP-2 boosted fusion rates to 94% in high-risk patients, compared to 81% with traditional bone grafts.

There’s also growing interest in motion-preserving alternatives. Dynamic stabilization devices act like a flexible brace for the spine. They don’t fuse the bones but limit excessive movement. Early data shows 76% success at five years for Grade I-II slips. That’s lower than fusion’s 88%, but it’s an option for people who want to avoid fusion entirely.

The global spinal fusion market is growing fast-projected to hit $7.8 billion by 2027. That’s not just because more people are getting diagnosed. It’s because better tools and techniques are making surgery safer and more effective.

How to Decide What’s Right for You

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Your choice depends on:

- How bad your slip is (Grade I-II? III-IV?)

- How much your daily life is affected

- Whether you have nerve symptoms

- Your age, weight, and smoking status

- Your tolerance for risk and recovery time

If you’re young, active, and have mild pain, stick with PT and lifestyle changes. If you’re over 60, have a Grade III slip, and can’t walk without stopping, fusion is likely your best bet. Newer techniques like TLIF with advanced spacers give you the highest chance of long-term relief.

One final thought: don’t chase the X-ray. A Grade II slip doesn’t mean you need surgery. A Grade I slip doesn’t mean you’re fine. Pain and function matter more than numbers on a scan. Work with a spine specialist who listens-not just one who pushes the latest device.

Can spondylolisthesis heal on its own without surgery?

In mild cases (Grade I or II), yes-especially in younger patients. The slip itself won’t reverse, but symptoms often improve with physical therapy, activity modification, and time. The spine adapts, muscles strengthen, and pain decreases. But if the slip is severe or nerve symptoms are present, healing without intervention is unlikely.

Is walking good for spondylolisthesis?

Yes, but with limits. Walking is low-impact and helps maintain mobility. Many people find walking bent slightly forward (like pushing a shopping cart) reduces pain. Avoid long walks if they trigger leg cramps or numbness. Short, frequent walks are better than one long one. If walking becomes painful or forces you to stop, talk to your doctor.

Can I still exercise with spondylolisthesis?

Absolutely-but avoid high-risk movements. Skip heavy squats, deadlifts, gymnastics, and anything that arches your back forcefully. Focus on swimming, cycling, core stability exercises, and hamstring stretches. A physical therapist can design a safe routine. Many people return to fitness after rehab, just with modified techniques.

Does spondylolisthesis get worse with age?

It can, especially if it’s degenerative. As discs and joints wear down, the slip may progress slowly over time. But not everyone’s condition worsens. Some people stabilize after the initial slip. The key is managing risk factors: weight, posture, activity level, and smoking. Regular check-ups help catch changes early.

What are the risks of spinal fusion surgery?

Risks include infection, nerve damage, blood clots, and failure of the bones to fuse (pseudoarthrosis). Smokers and people with high BMI have much higher risks. Long-term, adjacent segment disease can develop in 18-22% of patients within five years, leading to new pain in nearby areas. Revision surgery is needed in 12-15% of high-grade cases.

Written by Felix Greendale

View all posts by: Felix Greendale