Renal Artery Stenosis Risk Assessment Tool

Risk Assessment

This tool helps identify patients who should be screened for renal artery stenosis before starting ACE inhibitors.

Based on guidelines from the American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology.

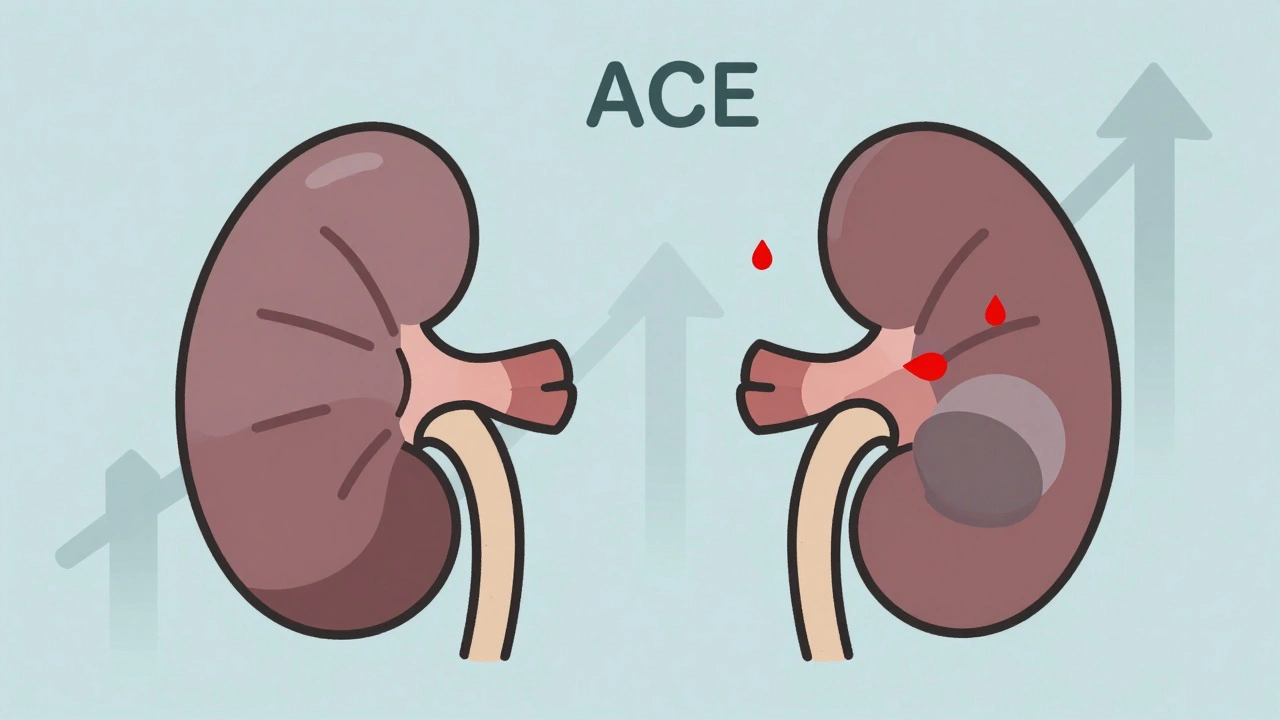

When your kidneys don’t get enough blood, your body tries to compensate by turning on a powerful hormone system called the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). This system raises blood pressure to force more blood through narrowed arteries. But if you take an ACE inhibitor while this system is already working overtime, you can accidentally shut down your kidneys’ last line of defense - and that’s dangerous.

How ACE Inhibitors Work (And Why That’s a Problem in Renal Artery Stenosis)

ACE inhibitors - like lisinopril, enalapril, and ramipril - block the enzyme that turns angiotensin I into angiotensin II. Angiotensin II is a potent vasoconstrictor. It tightens blood vessels, which raises blood pressure. That’s why these drugs are used to treat high blood pressure, heart failure, and diabetic kidney disease. But in a healthy kidney, angiotensin II also plays a quiet, critical role: it keeps the glomeruli (the filtering units) under enough pressure to work properly.

In renal artery stenosis, one or both renal arteries are narrowed - often by plaque buildup (atherosclerosis) or fibromuscular dysplasia. This reduces blood flow to the kidney. The kidney thinks it’s being starved, so it releases renin. Renin triggers the production of angiotensin II, which then constricts the tiny efferent arterioles leaving the glomerulus. This keeps the pressure high inside the filtering units, so the kidney can still filter blood even with low blood flow.

When you give an ACE inhibitor to someone with this condition, you remove angiotensin II. Suddenly, those efferent arterioles relax. Glomerular pressure drops by 25-30%. The kidney can’t filter anymore. Creatinine rises. Kidney function plummets.

The Difference Between Unilateral and Bilateral Stenosis

Not all renal artery stenosis is the same. If only one kidney is affected and the other one is normal, your body can usually compensate. The healthy kidney picks up the slack. That’s why ACE inhibitors can sometimes be used cautiously in this situation - under close monitoring.

But if both kidneys are narrowed (bilateral stenosis), or if you have only one functioning kidney and it’s narrowed, there’s no backup. The entire filtration system depends on angiotensin II to keep glomerular pressure up. Remove it, and both kidneys shut down together.

This isn’t theoretical. In a 1984 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 12 out of 15 patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis developed acute kidney failure within days of starting captopril. Since then, every major guideline - from the American Heart Association to the European Society of Cardiology - has listed bilateral renal artery stenosis as a hard contraindication for ACE inhibitors.

What Happens When You Take ACE Inhibitors With Renal Artery Stenosis?

The drop in kidney function doesn’t always happen right away. It usually shows up 7 to 10 days after starting the drug. That’s why guidelines say to check your creatinine level about 10 days after beginning an ACE inhibitor - and again after any dose increase.

A rise in serum creatinine of more than 30% from baseline is a red flag. It doesn’t mean the drug is working too well. It means your kidneys are failing. In most cases, stopping the ACE inhibitor reverses the damage. But if the low blood flow lasts more than 72 hours, the injury can become permanent.

A 2018 study of 1,247 patients starting ACE inhibitors found that 18.7% of those with undiagnosed bilateral renal artery stenosis developed acute kidney injury - compared to just 2.3% in patients without stenosis. That’s nearly 8 times higher risk.

ARBs Are Not a Safe Alternative

Some doctors think switching from an ACE inhibitor to an ARB (like losartan or valsartan) is a workaround. It’s not. ARBs block the same final step - angiotensin II’s action on receptors. They do the same thing to the efferent arterioles. The 2019 KDIGO guidelines and the 2002 American Heart Association statement both say ARBs carry the same contraindication. If ACE inhibitors are dangerous in renal artery stenosis, so are ARBs.

Who Should Be Screened Before Starting ACE Inhibitors?

You don’t need to test everyone. But if you have any of these, your doctor should consider checking for renal artery stenosis before prescribing an ACE inhibitor:

- Sudden, unexplained rise in creatinine

- Accelerated or resistant high blood pressure (especially if you’re over 50)

- An abdominal bruit (a whooshing sound heard with a stethoscope over the belly)

- Unexplained kidney shrinkage on imaging

- History of atherosclerosis in other arteries (heart, legs, brain)

Studies show that about 6.8% of people with high blood pressure and kidney problems have significant renal artery stenosis. That’s not rare. And it’s often missed.

How Doctors Test for Renal Artery Stenosis

The first-line test is a renal artery duplex ultrasound. It’s non-invasive, doesn’t use radiation, and has 86% sensitivity and 92% specificity for detecting stenosis that’s severe enough to affect kidney function. If it’s unclear, doctors may follow up with a CT angiogram or MR angiogram.

Screening isn’t routine for everyone. But if you’re over 60, have diabetes, smoke, or have plaque in your heart or leg arteries, and you’re being considered for an ACE inhibitor, ask your doctor if stenosis has been ruled out.

What If You’re Already on an ACE Inhibitor?

If you’ve been taking an ACE inhibitor for months or years and your kidney function has been stable, you’re likely fine. The danger comes when the drug is started in someone with undiagnosed stenosis.

But if your creatinine suddenly jumps - especially after a dose increase - don’t assume it’s just aging or dehydration. Ask for a renal ultrasound. That rise could be your body screaming that something’s wrong.

What Are the Alternatives?

If you have bilateral renal artery stenosis or stenosis in a single kidney, your doctor will avoid ACE inhibitors and ARBs entirely. Other blood pressure medications are safer:

- Calcium channel blockers (like amlodipine) - they relax arteries without affecting kidney filtration pressure.

- Diuretics (like chlorthalidone) - help reduce fluid overload and lower pressure.

- Beta-blockers (like metoprolol) - reduce heart rate and cardiac output, lowering pressure.

In some cases, if the stenosis is severe and causing uncontrolled high blood pressure or worsening kidney function, doctors may recommend angioplasty with stenting. But studies like the 2017 ASTRAL trial showed that for most people, medical management with the right drugs works just as well as surgery - and carries less risk.

The Bottom Line

ACE inhibitors are powerful, life-saving drugs - for most people. But in renal artery stenosis, they’re not just ineffective. They’re dangerous. The contraindication isn’t outdated. It’s not theoretical. It’s backed by decades of research, from micropuncture studies in dogs to large human trials.

Doctors aren’t perfect. A 2020 study found that over 22% of patients with known bilateral renal artery stenosis were still being prescribed ACE inhibitors in primary care. That’s a gap in safety.

If you’re being prescribed an ACE inhibitor and you have risk factors for renal artery disease - especially if you’re over 60, have a history of vascular disease, or your kidney function has been unstable - speak up. Ask: "Have you ruled out renal artery stenosis?" A simple ultrasound could prevent irreversible kidney damage.

Written by Felix Greendale

View all posts by: Felix Greendale